Cybersecurity Frameworks Explained

Cybersecurity frameworks can seem complex at first glance, but they’re actually quite helpful when navigating the ever-changing array of IT security threats and possible solutions.

Cybersecurity frameworks started appearing on the radars for IT and Cybersecurity professionals around 2013, arriving from multiple sources. Some of the earliest examples include:

- The Australian Government’s Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) identified the “top 4 controls” found to be effective at mitigating the most common cybersecurity threats. By 2017, this project had evolved to a baseline known as The Essential Eight, which continues to be updated and promoted in the present day.

- In a brief presentation at the RSA Conference 2014, industry veteran Tony Sager gave a first-hand account of how the Critical Security Controls (CSC) movement unfolded in the United States. From its roots in 2008 as “a little afternoon project” involving ten intelligent people working at the National Security Agency to an initial top 10 list shared informally within the information security industry, it evolved to a broader and more formal coordination through the SANS Institute — the “SANS Top 20.” After that, the CSC were moved from SANS to the stewardship of the independent, non-profit Council on Cybersecurity starting in 2013, then transferred in 2015 to the Center for Internet Security (CIS), which continues to host and manage the CIS Critical Security Controls today.

- In February 2014, the US National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST) released the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF 1.0), which introduced a now well-known list of five CSF Core Functions (Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover). A decade later, February 2024 saw the release of NIST CSF 2.0 and the addition of an important sixth CSF Core Function: Govern.

What’s the ongoing motivation behind these cybersecurity frameworks and control initiatives? What needs do they help address for IT and cybersecurity professionals? One of the biggest challenges is cutting through the complexity of hundreds of cybersecurity solution categories — from literally thousands of solution providers, not to mention countless open-source alternatives — that have already been made available and continue to be introduced.

Certainly, this level of innovation and investment is a testament to the importance of the cybersecurity problem that technical professionals are dealing with. Conversely, having such an overabundance of options can make it painfully difficult to sort through and make the necessary choices for the mix of controls that represent the best fit for a given organization’s specific context. This includes:

- Your computing infrastructure

- Your applications and data

- Your users

- Your industry

- Your regulatory requirements

- Your mission and strategy

- Your staffing and budgets

- Your appetite for risk

Today’s IT and cybersecurity professionals face the challenging task of figuring out not only what to do but also persuading others that it’s worth doing — then actually doing it and sustaining those activities over time in a dynamic, complex environment.

The core concept behind cybersecurity frameworks and critical security controls movements is for organizations to simplify this complex process by using the power of the community to identify a small number of security controls that are proven to have a high payoff at preventing known attacks.

CIS Critical Security Controls (CSC) v8.1

The latest CIS Critical Security Controls (version 8.1) describes 18 technical controls — which then expand into 153 specific actions to be implemented (the Center for Internet Security refers to these actions as Safeguards):

| CIS Critical Security Controls v8.1 | # of Safeguards |

|---|---|

| CIS 01: Inventory and Control of Enterprise Assets (e.g., devices, servers) |

5 |

| CIS 02: Inventory and Control of Software Assets (e.g., operating systems, applications) |

7 |

| CIS 03: Data Protection | 14 |

| CIS 04: Secure Configurations of Enterprise Assets and Software | 12 |

| CIS 05: Account Management | 6 |

| CIS 06: Access Control Management | 8 |

| CIS 07: Continuous Vulnerability Management | 7 |

| CIS 08: Audit Log Management | 12 |

| CIS 09: Email and Web Browser Protections | 7 |

| CIS 10: Malware Defenses | 7 |

| CIS 11: Data Recovery | 5 |

| CIS 12: Network Infrastructure Management | 8 |

| CIS 13: Network Monitoring and Defense | 11 |

| CIS 14: Security Awareness and Skills Training | 9 |

| CIS 15: Service Provider Management | 7 |

| CIS 16: Application Software Security | 14 |

| CIS 17: Incident Response Management | 9 |

| CIS 18: Penetration Testing | 5 |

For those who need it, CIS also provides a mapping from the Critical Security Controls to the more generalized (and more complex) NIST Cybersecurity Framework.

How to Prioritize the Safeguards

You can’t implement every safeguard, everywhere, all at once — so which ones should be first? Recognizing that no organization can simply flip a switch and implement all of the 153 CIS Safeguards in support of the 18 CIS Critical Security Controls at the same time, the Center for Internet Security describes three distinct “Implementation Groups” (IGs) — ranging from basic cybersecurity hygiene (CIS IG1) to a mature cybersecurity program (CIS IG3).

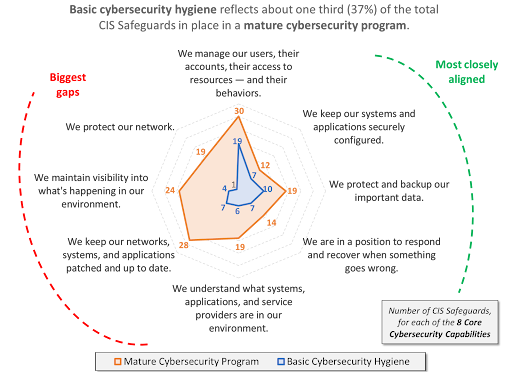

The following chart shows Aberdeen’s take on the differences between these two implementation groups, based on the total number of CIS Safeguards that align with what we refer to as eight Core Cybersecurity Capabilities.

Source: Adapted from CIS Critical Security Controls (version 8), Aberdeen, October 2023

The Core Cybersecurity Capabilities where basic security hygiene and mature cybersecurity programs are most closely aligned generally reflect what many would refer to as basic blocking-and-tackling:

- We manage our users, their accounts, their access to resources — and their behaviors.

- We keep our systems and applications securely configured.

- We protect and back up our important data.

- We are in a position to respond and recover when something goes wrong.

In contrast, the Core Cybersecurity Capabilities where the two implementation groups have the biggest gaps are much more pronounced in dimensions of organization-wide visibility and monitoring, such as those found in an advanced Network Operations Center (NOC) or Security Operations Center (SOC).

The CIS CSC are popular, for a reason. They can help IT and cybersecurity practitioners navigate the rich, complex, and ever-changing array of cybersecurity technologies more quickly and distinguish between the “useful many” and the “vital few.” You and your organization can use the CIS CSC as a jumping-off point, and adapt them in the way that works best for your environment and your appetite for risk.

CIS Critical Security Controls: Focus on 8 Core Capabilities

The mix of technical controls and safeguards will continue to evolve in response to the ever-changing landscape of cybersecurity-related threats, vulnerabilities, and exploits — but performing well at these eight foundational capabilities will serve the organization again and again over the long term.

In that spirit, the eight core capabilities enabled by the 18 CIS Critical Security Controls and the 153 associated CIS Safeguards are as follows:

- We understand what systems, applications, and service providers are in our environment.

- CIS 01: Inventory and Control of Enterprise Assets (e.g., devices, servers)

- CIS 02: Inventory and Control of Software Assets (e.g., operating systems, applications)

- CIS 15: Service Provider Management

- We keep our systems and applications securely configured.

- CIS 04: Secure Configurations of Enterprise Assets and Software

- We keep our networks, systems, and applications patched and up to date.

- CIS 07: Continuous Vulnerability Management

- CIS 10: Malware Defenses

- CIS 16: Application Software Security

- We protect and back up our important data.

- CIS 03: Data Protection

- CIS 11: Data Recovery

- We protect our network.

- CIS 12: Network Infrastructure Management

- CIS 13: Network Monitoring and Defense

- We manage our users, their accounts, their access to resources — and their behaviors.

- CIS 05: Account Management

- CIS 06: Access Control Management

- CIS 09: Email and Web Browser Protections

- CIS 14: Security Awareness and Skills Training

- We maintain visibility into what’s happening in our environment.

- CIS 08: Audit Log Management

- CIS 15: Service Provider Management

- CIS 18: Penetration Testing

- We are in a position to respond and recover when something goes wrong.

- CIS 17: Incident Response Management

- CIS 11: Data Recovery

Putting the Structure to Work

Here’s how IT and cybersecurity practitioners can use this structure to define and develop their organization’s cybersecurity programs more confidently:

- Think more broadly about your organization’s cybersecurity needs, using Aberdeen’s eight Core Cybersecurity Capabilities in the form of questions. For example, in what ways are you currently managing your users, their accounts, their access to resources, and their behaviors? In what ways are you currently protecting and backing up your important data? And so on.

- Do a gap analysis. Responding to these questions will result in an organized inventory of your organization’s current cybersecurity controls and safeguards. You can then compare these with community-based recommendations, such as the 153 safeguards suggested by the CIS Critical Security Controls.

- Evaluate and prioritize your next steps. Based on the gap analysis, you can more easily evaluate the costs (e.g., build vs. buy, products vs. services) and benefits (e.g., reduction in risk, operational efficiencies, business enablement) of implementing the most relevant incremental controls and safeguards, and prioritize which ones to pursue.

Aberdeen Strategy & Research has also made available a formal Knowledge Brief, A Practical Guide for IT Pros: Do You Have These 8 Core Cybersecurity Capabilities?, and an informal, conversational podcast on these topics.

NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0

Many IT and Cybersecurity professionals use the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF) to help them establish and execute their organization’s cybersecurity program.

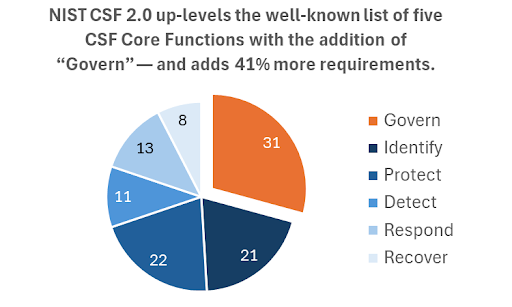

First released in February 2014 (CSF 1.0), the NIST Cybersecurity Framework was updated in February 2024 (CSF 2.0). Among other things, NIST CSF 2.0 expanded and up-leveled the well-known list of five CSF Core Functions (Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover) with an important sixth: Govern.

NIST CSF 2.0 Adds a Sixth Function

| Govern | Our cybersecurity risk management expectations, strategies, and policies are clearly established, well-communicated, and closely monitored. |

|---|---|

| Identify | Risks to our computing assets (e.g., hardware, software, data, systems, facilities, services, people, supply chains) are identified and prioritized, consistent with our established governance. |

| Protect | Capabilities (i.e., policies and controls) are in place to prevent or lower the likelihood and negative impact of adverse cybersecurity events and to increase the likelihood and positive impact of upside business opportunities. |

| Detect | Capabilities are in place to enable the timely discovery and analysis of anomalies, indicators of compromise, and other events that might reveal that cybersecurity attacks and incidents are occurring. |

| Respond | Capabilities are in place to contain the effects of detected cybersecurity attacks and incidents; these include investigation, analysis, mitigation, reporting, and communication. |

| Recover | Capabilities are in place to enable the timely restoration of our computing assets and recovery of operations affected by a cybersecurity incident or event. |

Source: Adapted from NIST CSF 2.0, Aberdeen, October 2024

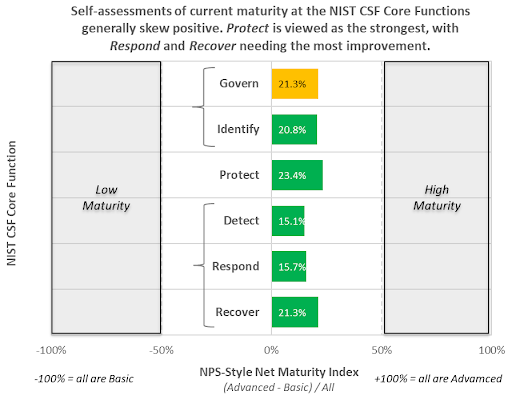

Aberdeen’s benchmark research shows that across all respondents, self-assessments of current maturity at the six NIST CSF 2.0 Core Functions generally skew in the positive direction. Many IT professionals view Protect as the strongest area, reflecting a traditional focus on technical controls. They see Respond and Recover as needing the most improvement, which highlights the complex and dynamic nature of modern computing infrastructure and the unfortunate successes of cybersecurity adversaries. Identify lays the foundation for Govern, which explains why professionals perceive these two areas as closely aligned in their current maturity, despite their differences.

Self-assessments of current maturity at the six NIST CSF 2.0 Core Functions generally skew positive

Indeed, it’s worth noting that this level of maturity comes after more than a decade since the introduction of NIST CSF 1.0. Without a doubt, the NIST CSF is complex! To enumerate, the six Core Functions in NIST CSF 2.0 are broken down into 22 categories, which in turn are broken down into 106 specific requirements:

- Govern: 6 categories, 31 requirements

- Identify: 3 categories, 21 requirements

- Protect: 5 categories, 22 requirements

- Detect: 2 categories, 11 requirements

- Respond: 4 categories, 13 requirements

- Recover: 2 categories, 8 requirements

The NIST CSF is generally held in high regard, but in Aberdeen’s view, it has contributed to a general confusion over activities versus outcomes. For one thing, suppose our annual cybersecurity budget requests are based on growing the maturity of our NIST CSF-based programs. In that case, we need to consider the scale of growth. This scale can be qualitative or pseudo-quantitative. The question arises: on what basis can the organization’s senior leadership team make resource allocation decisions? Is it purely based on intuition and gut feelings? Likewise, doing a better job at cybersecurity governance can help IT and cybersecurity practitioners speak more directly to the value of our NIST CSF programs in terms of the that justify investments: reduction in risk (cost avoidance), operational efficiencies (cost savings), and achievement of the organization’s strategic objectives (business enablement).

In Aberdeen’s view, NIST CSF 2.0 has served the market well with the addition of “Govern,” which promotes greater visibility and focus on cybersecurity’s strategic and business-oriented outcomes in addition to its traditional technical activities.

Changes to NIST CSF 2.0

NIST released CSF 2.0 in February 2024. It expands and upgrades the original five CSF Core Functions from CSF 1.0, which NIST released in February 2014. The five functions are Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover. The new version introduces an important sixth function: Govern. In Aberdeen’s view, this addition promotes greater visibility and focus on cybersecurity’s strategic and business outcomes. This change also emphasizes traditional technical activities. Furthermore, NIST CSF 2.0 adds 41% more specific requirements.

At a high level, governance is the process by which an organization’s cybersecurity risk management expectations, strategies, and policies are established, communicated, and monitored.

In smaller organizations, there isn’t always much distinction between who handles these two essential aspects of IT and cybersecurity. Whether the subject is networks, storage, servers, cloud services, endpoints, applications, data, or cybersecurity doesn’t matter. It’s not unusual for the same IT professional to handle both management and governance. Management involves technical activities. Governance refers to business decisions about those activities.

Organizations that are large enough to have dedicated cybersecurity staff tend to keep a clear distinction between the two aspects. Often, one team governs the business function known as cybersecurity. Concurrently, there is another team that manages cybersecurity-related people, processes, and technologies. This distinction is particularly evident in organizations with a dedicated cybersecurity leader.

Different organizations will naturally be at different stages of maturity regarding the connection between these two essential tasks. Either way, both cybersecurity governance and cybersecurity management have always been taking place. Unfortunately, it hasn’t necessarily been happening with the involvement of all of the appropriate players.

A Strategy Map to Connect Technical Activities to Strategic Outcomes

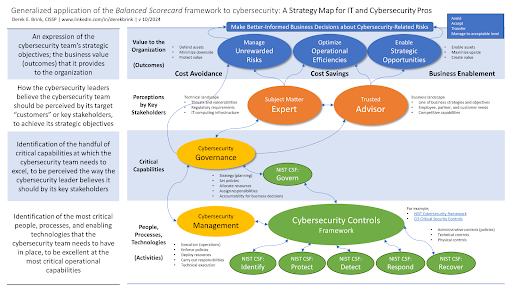

Aberdeen has been writing about how to connect technical activities to business outcomes since before the release of NIST CSF 1.0. “A Strategy Map for IT and Cybersecurity Pros” is a helpful visualization of Aberdeen’s application of the Balanced Scorecard framework.

Since 1992, organizations have used this framework to describe, communicate, and execute their strategies. It does this by focusing on the cause-and-effect linkages between technical activities and business outcomes. The framework is typically defined from the top down, starting with the strategic business outcomes in mind. However, it is always executed from the bottom up.

Source: Aberdeen, October 2024

The chart above shows how the four levels of the Balanced Scorecard framework connect. You can apply the outcomes, stakeholder perceptions, critical capabilities, and activities to cybersecurity in the following ways:

- Row 1: Outcomes — The raison d’être for the cybersecurity team:

- Manage unrewarded risks (cost avoidance)

- Optimize operational efficiencies (cost savings)

- Enable strategic opportunities (business enablement)

- Row 2: Perceptions — How the cybersecurity team should strive to be seen by key stakeholders:

- Subject-Matter Experts (technical skills)

- Trusted Advisors (business savvy)

- Row 3: Critical Capabilities — Functions at which the cybersecurity team must excel to deliver on perceptions and outcomes:

- Cybersecurity Governance (e.g., NIST CSF: Govern)

- Row 4: Activities — The people, processes, and enabling technologies needed for excellence in critical capabilities:

- Cybersecurity Management (e.g., NIST CSF: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover)

For ten years, the NIST Cybersecurity Framework emphasized the basic technical activities needed for effective cybersecurity. NIST grouped these activities into five core functions: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover. The release of NIST CSF 2.0 shows an ongoing improvement in cybersecurity practices. Adding a new focus on the Govern function is essential for proper oversight of cybersecurity actions.

Outside of their NIST-based cybersecurity programs, Aberdeen suggests that technical professionals also continue to expand and mature their skills. Two obvious examples to work toward are:

- Being seen not only as a subject-matter expert but also as a trusted advisor, and

- Identifying contributions from cybersecurity-related activities. Professionals should look beyond the traditional areas of cost avoidance, and also consider cost savings and business enablement.

For more information, check out the Aberdeen Knowledge Brief, Cheers to the Governor: A Practical Guide for IT Pros.

Takeaways

In Aberdeen’s view, frameworks are not a checklist to be strictly followed, but rather a faster path to considering the successful choices that others have made. Your organization should adapt a framework in the way that works best for your own environment, and for your own appetite for risk.